Salmon living in a river near Christchurch, New Zealand, are the descendants of winter-run Chinook salmon whose eggs were shipped to different places around the world more than a century ago – and they offer hope that the salmon can be restored to their traditional spawning grounds in California’s McCloud River.

Ironically, that happened because during the 1870’s, when railroad construction and hydraulic gold mining was devastating many salmon runs, the federal government established the first U.S. fish hatchery along the McCloud River, and later shipped some salmon eggs to New Zealand. When the hatchery was established, the tribe pledged to the salmon that they would always be able to return home.

It wasn’t until 2004, reviving a war dance that hadn’t been performed for more than a century, that the tribe got a message from the Maori people – “we have your salmon”.

Those young salmon, growing in the Rakaia River, are smaller than their ancestors but have remained genetically pristine and disease-free, as DNA testing showed.”These are the fish that would have grown up to be McCloud River salmon,” says chief Caleen Sisk. “You can’t look at Sacramento salmon and know which ones were supposed to be McCloud salmon. Those salmon in New Zealand are the ones we made that promise to.”

The salmon once were so numerous that tribal tales talk about how people could walk across the river on their backs. To help the salmon travel upstream to colder waters, they lit fires at night along the river, and carried fish in baskets on foot if there were obstacles along the way.

But many of the tribe members living around the McCloud River were displaced by the 602-foot-high Shasta Dam, built in 1947. It flooded the lower 26 miles, drowned many villages and sacred sites, blocked the salmon from returning home to spawn, and thus broke the tribe’s covenant with their salmon.

Then in 2004, the tribe learned that genetic descendants lived in New Zealand. And in 2010, 30 tribe members travelled there for their first salmon ceremony in nearly a century, where they were hosted by local Maori tribes; visited a hatchery, where they released salmon fry by hand; and danced and sang for four days on the banks of the Rakaia, asking the salmon for forgiveness. “During the ceremony, we saw the salmon jumping out of the water for us. I knew they were happy to see us, and they were ready to come home,” Sisk said.

The Maori tribes and Fish and Game New Zealand agreed that the Winnemem could import salmon eggs from the Rakaia and rear them in their own hatchery on the upper McCloud, where the fish could acclimate to the river’s waters.

Now they make that journey back home in California. In 2016, the tribe began an annual 300-mile prayer journey, working on new passage plans for the fish that avoid the dam. During the 300-mile Run4Salmon, participants run, bike, paddle, and ride horse along the path Chinook salmon once traveled from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta up the Sacramento River to the McCloud River.

“Before Run4Salmon, we figured out there hadn’t been a salmon ceremony in our Ohlone territory for over 200 years,” said Corrina Gould, a Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone activist. “We’re in a time where songs are coming [back], language is coming back, ceremony is coming back, and the return of the salmon is a part of that indigenous restoration we need for the future.”

In the summer of 2017, the Bureau of Reclamation allocated $200,000 to collect New Zealand salmon samples for DNA testing. The tribe raised an added $78,000 to support the project through a viral GoFundMe campaign.

In May 2022, the Winnemem Wintu signed a co-stewardship agreement with NOAA Fisheries, and last year, deposited 40,000 eggs in the McCloud River from California state hatcheries.

This year, with more than $2 million in private donations, the tribe bought back 1,080 acres of their ancestral lands.They started Sawalmem, a nonprofit with church status, to accept the land purchase because without federal recognition, the tribe can’t buy land in a trust.

“Our purpose is to restore the land the way it’s supposed to be, which means control burns, native plants, all the waterways totally restored,” said Michael Preston, executive director of Sawalmem and son of Chief Caleen Sisk. “And just make it an example of what the land is supposed to look like.”

As the Chinook salmon return and the tribe gets part of its ancestral lands back, the whole ecosystem will recover. Black bears, deer, and black spiders will return in greater numbers to the river.

“We’re working so hard to bring them back here, to their original waters and home, to give them their land back,” said biologist Marine Sisk, daughter of Chief Caleen Sisk. “It’s going to bring all of these animals that’ve been struggling to survive in a world without salmon. Salmon don’t just feed — they clean the rivers. We’ll be bringing a whole ecosystem back to health.”

Sources:

Winnimem Wintu Tribe Travels Across The Pacific To Recover Lost Salmon Species. HuffPost, Aug. 31, 2011

The Shasta Dam Killed Off This Tribe’s Salmon—Or So They Thought. YES Magazine, Nov. 9, 2017

The Winnemem Wintu won land back for their tribe. Here’s what’s next. Vox, Oct. 9, 2023

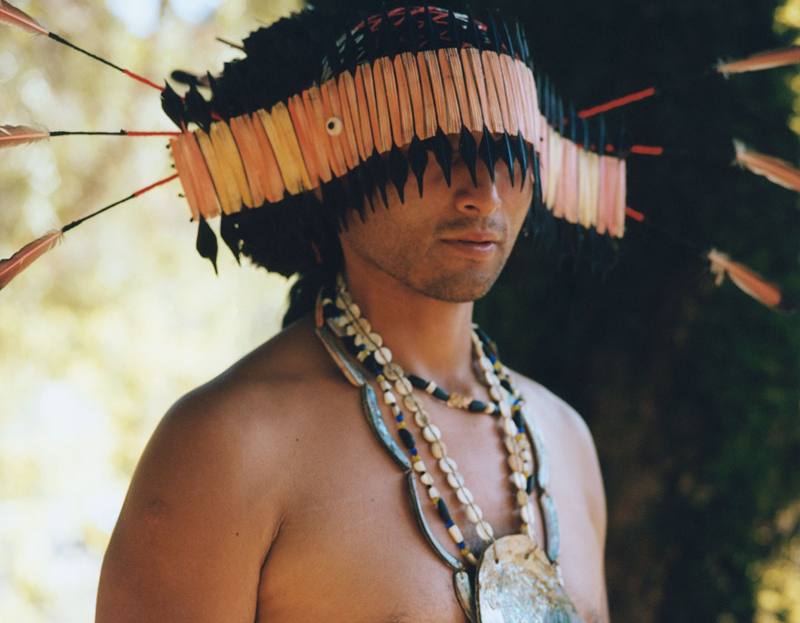

Cover image: Winnimem Wintu Tribe website